The pains of Lazzaro

Text of the Pastor Jene Havea*, published as "Lazarus Troubles" ** in Bible Trouble: Queer reading at the Boundaries of Biblical Scholarship, edited by TJ Hornsby and K. Stone, Society of Biblical Literature (United States), in January 2011. Freely translated by {([2]), volunteer of the Gionata project.

“And approaching, Jesus rolled the stone away from the door of the sepulcher. And immediately, who entered where the young [Lazzaro] was located, stretched his arm and made him raise, grabbing him by the hand. But the young man, looking at him, loved him and began to beg him to be with him.

And left the sepulcher, they entered the young man's house, since he was rich. And after six days Jesus told him what to do, and in the evening the young man came to him, wearing a sheet over his naked body. And remained with him that night, since Jesus taught him the mystery of the kingdom of God " (Extracted from Marco's secret gospel)*

The trauma of Lazzaro

John 11's story is full of trauma: with Jesus who is far from Bethany, when Lazzaro gets sick.

Malaise: Marta and Mary, the sisters of Lazzaro, send a message to inform Jesus that he who he loves with deep affection (Philein, 11,3.11) is sick.

Pain: the narrator and the sisters do not say what Jesus does in response.

Doubts: but we know that they, together with his brother, occupy a special place in the heart of Jesus, because he loves them in an unconditional and sacrificing way (Agapan, 11.5).

Hope: Jesus takes his time to answer.

Fear: Two days after receiving the message, Jesus leaves for Bethany. Indifference: in the meantime, Lazzaro has already died.

Lacrime: we do not know when exactly Lazzaro died compared to the moment in which Jesus received the message, nor how long he took him and the disciples to return to Bethany, but it is certain that Jesus arrived four days after Lazzaro's death.

Loss: Jesus first goes to Marta and Maria's house.

Questions: then he goes to the sepulcher and in front of the eyes and ears of those present, some of whom are his supporters and other opponents. And he asks Lazzaro to go out (from the tomb).

Raise: then Jesus tells some of them to dissolve (the bandages) to Lazzaro and to let him go.

Uncertainty: at that point, the narrator's attention moves from the risen body of Lazzaro to the growing resentment towards Jesus by the Jews.

Anguish: the story focuses on Jesus, as if Lazarus' risen body was no longer important.

Abandonment: Jesus recalls a dead body in life

Power: Jesus did not let Lazzaro rest in peace

Trouble: the story of Lazzaro, of a dead man who walks again, is disturbing.

Lazzaro's story poses several problems.

Queering Lazzaro, in prison

The story of the resurrection of Lazzaro has captured the attention of preachers, theologians, artists and scholars, who played it from a myriad of perspectives, appropriating it for the most disparate interests. My goal in this text is not to repeat those interpretations, but reread the history of Lazzaro in the light of the experiences experienced in the ocean part of the Pacific from which I come.

I will share some reflections born from the comparison with people held in the Pacific Islands that I met in 2007 at the Parklea prison, in the new South Wales, in Australia (see Taylor 2004, p. 54).

The participants in my weekly visits agreed that some of their names were reported: Amini, Tuifua, Samiu, Sione (X2), Va'ga, Filvision and Mali (other people participated occasionally).

I asked them to read Giovanni 11, to discuss the figure of Lazzaro in the courtyard of the prison, to stage their understandings during our meetings, to help me see this story through their tattooed bodies, wounded by knives, cicatrized, affected by firearms, perforated and violated.

The prisoners also created a rap with a surreal rhythm, entitled "The Gospel of Lazaros", whose texts changed to each execution. (The titles of the sections that follow resume phrases taken from that rap).

They told me that I didn't have a suitable language to rap, but they got to share some of their visions about Lazzaro's story and on what I saw in their bodies in the process of "dislegate Lazzaro".

Obviously, there is no single "as detained" understanding of the history of Lazzaro, just as there is not a single native, indigenous or Asian perspective (see Kang 2004).

In this honor chapter the multiplicity of their voices, trying to escape the imposition of dominant speeches that try to legitimize a control over the perspectives (see A. Jensen 2007).

This chapter will not echo the cry of Jesus "Lazzaro, come out!", But rather he will ask, with a certain dismay: "What the heck?"(See Althaus-Reid 2005, p. 7), speaking on behalf of Lazzaro. It is a text on the trouble of Lazzaro and how this story has also troubled us (as a group, for almost four months).

I give the story of Lazzaro following the definition proposed by Stephen Moore, according to which "Queer" is "A mobile sign that designates what opposes normal and natural, defining them by contrast, and at the same time what it lurks in the normal and natural to subvert and even perverted them - an opposition and subversion that favors, although not limiting itself, to the iridescent sphere of the sexual"(Moore 2001, p. 18; see Althaus-Reid and Isherwood 2007; Stone 2001, p. 117). [...]

Lazzaro, your condemnation is death

Some of the people held with whom I dialogue were condemned for murder; The families of the victims and their circles of friends live in anguish when my detained friends receive slight penalties. But my friends in prison in turn feel anguish when white men receive even lighter convictions for similar crimes.

In the prison context, death stings on several levels, and my detained friends underlined how they are affected by the lezzo of death in their understanding of the history of Lazzaro. For those in prison, the biblical passage of Giovanni 11 is above all a story of death and imprisonment in a dark tomb, from which relatives and friends are excluded.

Lazzaro receives a death sentence, and rotates in solitude, wrapped in bandages that prevent its decomposition, even from dead.

The sepulcher and the bandages of Lazzaro disturb my friends who caused the death of other people: one of them agitated on the ground, like a fish out of water, to show how the body in the decomposition of Lazzaro was imagined.

The story of Lazzaro simply speaks of death, not because there is hope in the resurrection, but because death and death sentences are concrete realities.

"Don't joke with death», The prisoners told me, because hope, for those who have a life sentence or death, is precisely in death itself. Death is always close, and they do not fear it as much as I fear it (cf. Byrne 1991, pp. 10-11).

The prisoners are easily identified with Lazzaro. The most violent criminals saw in his death a symbol of the possibility of escaping from imprisonment, a vision that frightened the small offenders, not ready to death, but that see in the tomb of Lazzaro a representation of the cell.

Some were even envious of Lazzaro, imagining that he had a sepulcher everything to himself.

For them, it would have been cruel if Lazzaro had had a "roommate" in the tomb - like when the prisoners have a cellmate - and he had risen, while the other did not.

The resurrection of Lazzaro therefore disturbed those prisoners who, despite having a life sentence, realize that only a few of them, not all of them, will be freed.

*The reverend jexe havea* is a methodist theologian originally from the Tonga islands and currently a researcher at the Charles Sturt University (Charles Sturt University, Australia). It is also Research Fellow at the Trinity Methodist Theological College (Methodist theological college Trinity, New Zealand). His publications focus on the decolonial and queer reading of the Bible, with particular attention to the indigenous voices of the Pacific. He has collaborated on numerous projects related to social justice, contextual theology and pastoral care in prisons.

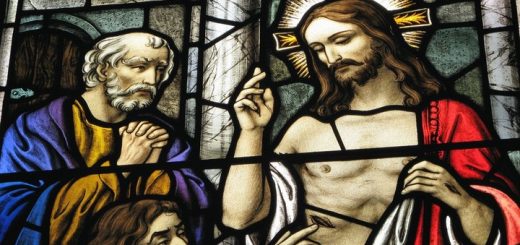

** This text reflects on the history of Lazzaro through the opinions expressed by the prisoners of the southern Pacific Islands that do not appreciate the way in which Jesus and the Giovanneo Gospel took advantage of the history of Lazzaro. They read the story on behalf of the "troubles of Lazzaro", which touches their reality in disturbing ways. The chapter put in touch the imagination of these prisoners with other imaginations, as with the secret gospel of Marco, with two works of art of Rembrandt and recent works by Queer readers. The result is a reading that allows Lazzaro to disturb the readers again.

***Marco's secret gospel, that Morton Smith stated was mentioned in a letter from Clement of Alessandria (Smith 1973, p. 447), although the authenticity of the Gospel and the letter is the subject of debate between scholars (see Jeffery 2007; ESler and Piper 2006, p. 48), what interests here is the eccentricity of the text.

Original text: Lazarus Troubles