Growing up as a gay Catholic. The author of "Wicked" talks about himself

Reflections by Gregory Maguire published on the New Ways Ministry blog on 17 December 2024, freely translated by Lorenzo Russo

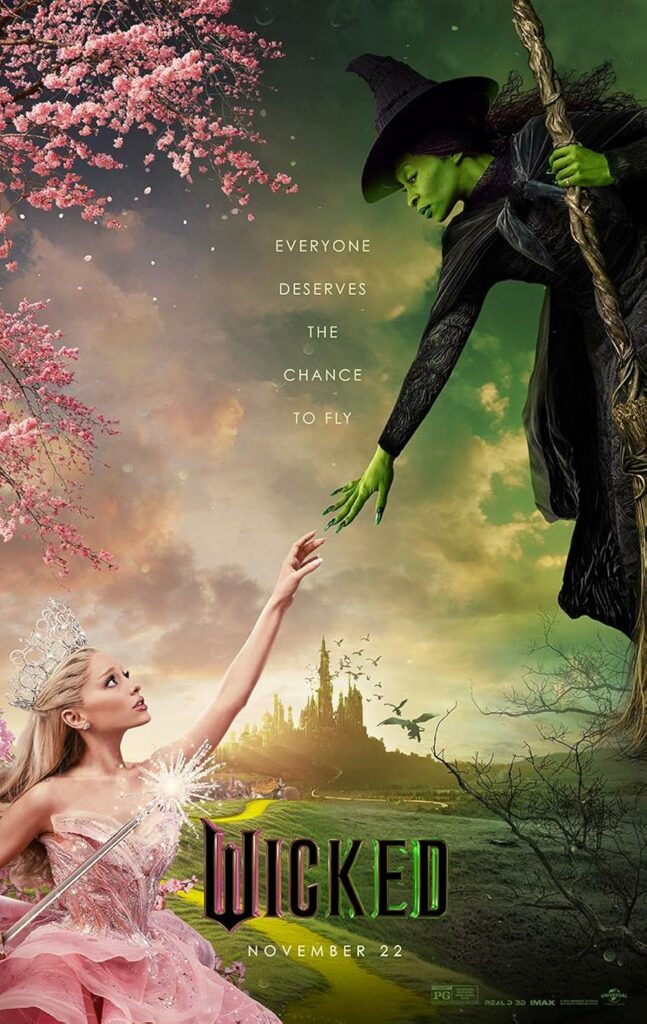

The guest post by today is by Gregory Maguire, author of over 40 books for adults and children, including the most famous: “Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West“ (Wicked: The Life and Works of the Wicked Witch of the West), a 1993 best-seller that was the inspiration for the musical “Wicked,” one of the longest-running shows in Broadway history. The musical was recently made into a successful film, with Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande as the protagonists, shown in cinemas everywhere.

As a gay Catholic who, along with her husband, Andrew Newman, raised three adopted children, Gregory taught a workshop on gay and lesbian families at the 2007 New Ways Ministry's Sixth National Symposium.

He also spoke about his family's life during a press event entitled “Five minutes with the Pope” during Pope Benedict XVI's visit to the United States in 2008.

I came to write the novel I called “Wicked: The Life and Works of the Wicked Witch of the West” in 1993. I had been thinking about it for a few years, but I was waiting until I felt I was capable enough for the task. I started the novel in London, on the day I turned 39.

My biological mother died in hospital a week after I was born, due to complications from childbirth. Despite having had a second mother who supported me entirely – it is surprising that she was my biological mother's childhood best friend – the crushing weight of the story of my birth weighed on me until that moment. Frankly, this burden still weighs on me. I didn't ask to be born, and my first mother didn't ask to die. But tragedy happened, and I had to live with a precise and inevitable sense of guilt.

I was born into a Catholic family, in a Catholic neighborhood – I was under the impression that most neighborhoods in mid-century Albany, New York were Catholic.

So I toiled throughout my childhood, with difficulty: inhaling the concepts of duty, of moral debt, of the responsibility of shouldering everything; and exhaling the fear that I would not be suited to the task that God seemed to have assigned me.

What task? That of living a sufficiently virtuous life, and doing good to others, so that I could somehow make up for the cost of my existence. I felt, and at the time I think I could say I was about twelve years old, I felt that my life should be twice as useful, in order to reward the spirit and soul of my late mother, who I believed was watching over me and my children. my three older brothers.

But at about sixteen years old and when the first signs of attraction towards other males began to appear, I fell prey to a torment of guilt. Was this why my mother died, why I would inevitably grow up queer-inverted-defective? What a cruel joke. The three “i's”, I reflected afterwards: illegal. Immoral. Infected (editor's note: infected to keep the initial “i” from the English “ill”).

I suppressed the growing sense of horror for as long as I could. I refused, I think; I couldn't be sure. And in my generation, at least in my Irish Catholic environment, the concept of “experimentation” was rarely discussed, let alone involved in it.

I mean, if heterosexual sexual practice wasn't mentioned by parents to teenagers, then, the possibility or even existence of homosexuality wasn't even whispered in locker rooms. I think many young people growing up today in an era of accessibility and identity politics can't imagine how abandoned, derelict, a gay kid in a Catholic high school might feel. As lonely as a green-skinned Elphaba, alone without her kind in a world of quietly ordinary citizens.

As I began to be able to read reasonably well, and understood the story of Oscar Wilde and what some (few) male kids did when they mocked the more sensitive or queer-reading males among us (I was rarely the target, luckily for me), the reality of what it all really meant--when it came to love, to passion, to promise--seemed like a towering black slate board on which no one, ever, had written a legible word. I knew about Michelangelo and maybe Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde. But I didn't personally meet anyone who was gay and out until I graduated from college – although I certainly ran into people who responded to affection and even courtship, including some men who loved me, in some way.

What helped me survive this bizarre blizzard of ignorance was the very thing that threatened me the most: my Catholic faith and identity.

I'm not going to defend or even define what my faith means to me now. I have long come to the conclusion that this is a task beyond my ability to explain. However, my understanding of how devout or skeptical I am fluctuates with all the geolocalization of an intractable electron, as stated by the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle.

But I can say that Being Good seemed to me to be at least twice as necessary as the church's teaching required, as Jesus required, due to the fact that I had to be good to myself and to my late mother, too.

I considered suicide, although not as intensely. The church taught that suicide was a mortal sin. Not even finally being reunited with my mother in heaven made this solution impossible. I also read “Death by choice” by Daniel C. Maguire (no relation). A highly respected theologian, he did not provide me with a way to make such a choice. Furthermore, I grew up in an era when Catholic help counseling offices had comforting posters stating that “God does not create waste,” a black pride slogan that was helpfully repurposed for more or less any high school moral crisis. Catholic. I believed in the goodness of God and the mystery of God's plan, and the sacred grace of discernment. I realized I had no options but to hold on, push through, and figure out what God had in store for me, something no dear nun or priest could name. And no parent would dare mention it in a speech.

So I sublimated my pain and my sense of isolation. Of course I did. Many of us do. But because I grew up in a family that loved writing and reading, and funny stories over dinner, in a family whose only real privilege was a multitude of library cards between the nine of us, I read to survive. Yes; It wasn't the pious nuns and noble priests, the hard-working and emotionally shy parents who saved me. It was the library.

I read about Aslan and the suffering creatures of Narnia, frozen in the White Witch's endless winter. I saw Aslan's forgiveness of the sinner, Edmond, I cried for how Meg Murray, in “A Wrinkle in Time,” was able to save her little brother through the power of love (with plenty of Christian symbolism to remind her of what she was capable of )

And I understood how keeping a diary could build the heart and mind of a writer thanks to “Harriet the Spy” by Louise Fitzhugh. I bought a secret diary, I started to observe the world, and thus (finally) to understand myself and come out. I taught myself to be honest, and to honor honesty, even if it was excruciating to put some thoughts out loud (on the secret page).

And in this way my being a Roman Catholic and my being gay, a pairing of seemingly irresolvable characteristics, were joined by a third identity: that of being a writer.

Which leads us, through Narnia and through love, to my life in England when I turned 39, and how I began to feel that my time had come. If I were one day older than my mother ever was—she died at 38—then I would be, by definition, an adult. (No one ever considers becoming older than their mother.) Having started out as a children's author, I felt I was old enough to now write an adult novel. I put aside my fear and hesitation, bought a new notebook, and began writing “Wicked” by hand. It was published when I was 41, almost 30 years ago.

Is “Wicked” about being gay, is it about being Christian in any way? Not explicitly. But I really tried to insert into the fabric of my anthropological gaze towards L. Frank Baum's happy kingdom of papier-mâché, nonsense, and variety shows something of the moral seriousness of Middle Earth and Narnia. First of all, I demanded a faith in Oz - a boundless faith in Oz. Not a magical faith, as in Narnia, not a faith of miracles and divine interventionism, but a human faith, practiced and often abused. And more than a single faith, because my Oz was meant to emulate our real world with its crusades and beliefs, its frictions and its paradoxes.

I also called for more romantic possibilities for the people of Oz, although I suggested this in a subtle way. Elphaba's son Liir has a same-sex romance (in the sequel “Son of a Witch”), and when we meet him again halfway through “The Witch of Maracoor” five books later in my saga, Levi and Trism are on the middle-aged, and have a home. When people ask me if Elphaba is based on me, I say that every strength of Elphaba's ambition is my ambition, and almost every weakness is a self-portrait. But Liir- who is inept, confused, crybaby, romantic, a foot soldier on his way to his own Calvary, probably- Liir is just me.

Like Tolkien, whose Christianity came across Middle-earth, I have tried to indicate the strength, the value, the danger of religious fervor in Oz without preferring one belief system over another. I tried to be honest. One of Elphaba's main motivations in the second half of the novel is the search for forgiveness, a project complicated by the fact that she is not sure if she has a soul. Additionally, I have given the citizens of Oz a greater variety of affective preference, and I have tried to avoid pathologizing my beloved characters, and to avoid assigning obvious or direct causes for why people are the way they are.

If you ask “Is there a Gelphie-type romantic affair—a crush between Galinda and Elphaba?”—I find that I don't know the answer. If you can, answer as best as you can to your satisfaction. Your guess is as good as mine.

Many things are unknown, such as the path of an electron around the nucleus of an atom. In order to have conversation, and to provide us with a false sense of stability in a universe whose planets swing as wildly as electrons do, we make blanket statements of certainty about this or that. This gives us a provisional and temporary foothold. We'll probably change our minds sooner or later. In the end, the real challenge is to accept the mystery of the unknown, and reject our instinct to categorize, to divide the world between us and them, good and bad, me and you. (Straight and gay, too. Devotees and non-practisers). If I can't even fully know myself, how can I say I know you? If I can't be sure whether I'm a person of faith or a person of shaky faith, or no faith, how can I be sure of who you are, and what you believe in, or a home you want, or what you're capable of?

What “Wicked” tries to do is be patient with ambiguity. In the words of the title of philosopher Alan Watts' book, “The Wisdom of Insecurity” – another literary work that helped keep me effective when I was about to start college. I could do it. I could keep my balance in the air. I could make something of myself, and repay my moral debt. I could, perhaps, defy gravity a little. For a while. And by writing “Wicked,” and my other forty or so books, I could try to provide comfort to others who are looking for the foothold they were raised to rely on, but can't find it.

We become each other's balustrade.

In the opening paragraphs of “Wicked,” which I recently needed to revisit, I notice that when I describe the Flying Witch, Elphaba does not ride her broom the way a polo player would ride a horse, or she sits side-saddle like a gentlewoman on a fox hunt. No. She uses the broom as a balustrade. This way of flying is replicated in both the stage musical and the film, mimicking my description in the novel. Elphaba in mid-air uses the broom as a handhold. For a moment, she invents her own handrail.

And as soon as possible the time will come for her to be a support for someone else. As, I believe, we all aspire to become.

Original text: On Elphaba and Growing Up a Gay Catholic: 'Wicked's' Author Reflects