Quando il coming out irrompe in famiglia

Text by Michael C. LaSala* taken from Coming Out, Coming Home: Helping Families Adjust to a Gay or Lesbian Child, Columbia University Press, 2010, freely translated by the Gionata Project volunteers

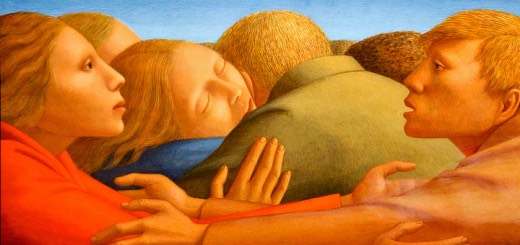

"If family were a fruit, it would be an orange: a circle of segments, close but separable, each unique and distinct” Letty Cottin Pogrebin

For some girls, it might have started with a crush on their older sister's best friend, or an unusual feeling while watching Xena, Warrior Princess on television. For some kids, it might have started with a fantasy of taking a bath with a friend or a strong desire to caress their gym teacher's bearded cheek.

Initially, these young people may not have given much thought to these impulses—they are often too young to understand their meaning. But as they grow up, there comes a time when they realize, with a sense of dread, that there is something wrong with those feelings—horribly wrong.

These impulses seem to distance them from everything they know, making them feel like boats adrift in a cold, dark, dangerous sea. Above all, these young people want to be like others, to feel accepted and appreciated by their peers.

But they soon realize that if anyone discovered their desires, they would be ridiculed and marginalized. They may lose everything: friends, respect from teachers and classmates, and most frighteningly, they may lose the love of their parents.

Now imagine that you are the parent of one of these boys or girls. Perhaps you've noticed that your daughter, with her tomboyish nature, doesn't seem to be as interested in boys as her older sister did at the same age and that she has a particularly intense friendship with her neighbor.

Or you may realize that your sensitive son prefers helping his mother around the house rather than playing football outside with the other kids. Like a summer breeze, a thought touches you: “Does it mean that… could it mean that…?”. But, before you can even complete it, the idea vanishes, light as that breeze. You try to ignore the anxiety that this thought has left you and try to forget it.

During adolescence, a truly complicated period for many families, young people begin to test their independence. They often question the values and ideas they grew up with to build their own identity.

However, it is a mistake to consider the development of a boy or girl an isolated moment. Sociologists and family therapists have identified stages of family development, in which mutual relationships evolve as children mature (Carter and McGoldrick 1999; Hill and Rodgers 1964).

In families with adolescents, relationships between parents and children must become more flexible to respond to children's growing needs for autonomy and their need to explore the world outside the family (Garcia-Preto 1999).

One of the biggest challenges for parents is finding a balance: giving their children the freedom to develop their own identity while still keeping them safe. It is certainly not an easy task.

Parents often face a whirlwind of emotions at this stage. They are anxious at the thought of their children spending more and more time away from family, exposed to dangers such as drugs and alcohol, and away from adult supervision.

These fears can be projected onto children, who in turn react: some internalize their parents' anxiety, while others forcefully reject it. It's no surprise that this is a complex time for many families—and that's before we even broach the topic of sexuality.

The first signs of sexual urges bring with them a confusing mix of embarrassment, anxiety and pleasure. For most adolescents, when hormones begin to kick in, the opposite sex, previously viewed with neutrality or contempt, becomes a source of fantasy, mystery, anguish and frustration.

Teens begin to recognize their sexual attractions and try to relate to others in new ways. Parents observe this change with a combination of amused pleasure—reminiscing about their first loves—and a sense of regret at seeing their “babies” grow up too quickly.

Some parents dream of the day when their children will get married and have families of their own, carrying on the family line. Others, however, are assailed by more concrete fears, such as the risk of unwanted pregnancies or sexually transmitted diseases.

These worries lead them to become overprotective, triggering anger and frustration in their children. “You worry too much!”, “You never give me enough freedom!”, “You treat me like a child!” are phrases that often echo in this period.

However, for approximately one in ten boys and girls, these family dynamics become even more complex. These young people do not live in a world that embraces their nascent sexual maturity. On the contrary, many of them feel isolated, alienated from a society that openly celebrates only heterosexuality.

Today's families are faced with the difficult task of managing their children's sexuality in a world that approves and recognizes attraction to the opposite sex.

Whatever their romantic or sexual problems, heterosexual men and women and their families can find guidance and potential solutions in art, media, psychology and other fields. Because they live in a society that supports heterosexuality, parents and children can easily access resources that help them understand, accept, and even celebrate these growing impulses and attractions.

There are opportunities within families, schools and communities to openly discuss with young people the risks of heterosexual sex, such as unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases, and how to avoid them. Furthermore, young heterosexuals can confidently look to the future, expecting legally and socially recognized love and marriage—ways to satisfy their desire for sexual fulfillment without risk or taboo.

However, approximately one in ten young people do not enjoy the privilege of living in a world that embraces their emerging sexual maturity. As Joelle, a young university student, who felt a strong sense of alienation when she realized she was attracted to other girls, recalled:

"I would say it all started in third grade. I felt I wasn't like other children. For long periods, I would just sit in class doing nothing, thinking, “God, I feel so different.”. "

The same goes for Mike, a young teacher who, after realizing he was gay, attempted suicide:

"When I was twelve, watching pornography I was attracted more to male bodies than female… it was just something I thought, no one knew except me. I think I understood it very young, around ten or eleven years old. It felt normal inside me, but I was very, very scared that someone would find out."

Many of the prevailing models of lesbian and gay identity development describe coming out as a predominantly individual experience, beginning with the anxiety-inducing awareness of being different from one's peers (Cass 1979; Coleman 1982; Troiden 1989). Troiden uses the term sensitization to describe this early phase of gay people's identity development, and listening to the stories of the sixty-five young people interviewed for this study, this term clearly resonated.

However, in interviewing gay and lesbian youth and their parents, I have found that there is a family process related to, but different from, the stages of family development identified by Carter, McGoldrick, and others. To use Troiden's concept, the first of these phases is what I call the “family awareness phase.”

As with the sensitization phase described by Troiden, the family sensitization period occurs from the moment boys and girls begin to understand that there is something different about them, often without knowing why, until about three months before to come out to their parents.

What makes this a family phase is the interaction between the young person's awareness of the stigma they experience, the emotional distance they experience from their parents, and the latter's suspicions.

As the previous quotes suggest, dealing with fears of shame, ostracism, and rejection is a central theme in the lives of the adolescents and young adults I interviewed for this research.

Once parents learn that their children are lesbian or gay, they too must face the fear of harsh judgment from those who would blame them for their children's homosexuality. However, shame and stigma are not the heart of the whole story.

The memories of these families reveal the strength and healing potential of family bonds, which resist the weight of guilt, anxiety and even social condemnation.

*Michael C. LaSala is an American clinical social work expert and family therapist with over 35 years of experience. He taught at Rutgers University, where he directed advanced programs in social work, and in 2017 received an award for his contributions to social justice. He is the author of Coming Out, Coming Home: Helping Families Adjust to a Gay or Lesbian Child (2010), a book based on research funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. The book offers practical strategies to help families manage the coming out of gay or lesbian children, promoting understanding and strengthening family relationships. Since 2024, he has been dean of the School of Social Work at Simmons University.

Original text: Coming Out, Coming Home: Helping Families Adjust to a Gay or Lesbian Child