What the traces of queer lives that survived Nazi persecution tell us

Text by Elsa Fischbach, published on the website of the LGBTIQ+ Center CIGALE (Luxembourg) on 31 January 2023. Freely translated by the volunteers of the Gionata Project.

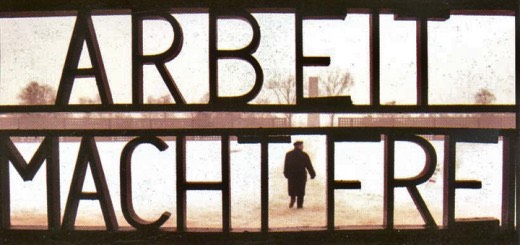

Memory implies knowledge. This article is dedicated to Remembrance Day (which is celebrated on January 27), and explores the traces left by Queer lives in the context of National Socialism.

One of the most studied aspects is the persecution of homosexual men. As early as 1871, the German Empire had introduced paragraph 175 of the penal code, which criminalized homosexual acts between men. Under the Nazi regime, this legislation was further tightened, leading many homosexual men to concentration camps.

Marked with the pink triangle, they were relegated to the lowest rung of the camp's hierarchy. The intense homophobia and stigmatization of the time meant that very few survivors dared to talk about their homosexuality after the end of National Socialism.

However, the persecution of homosexual men is relatively well documented thanks to historical archives. The situation is different for other queer identities, such as queer women and transgender people. Although they were not directly persecuted for their identity, these people did not fit into the National Socialist worldview. Many were deported to concentration camps as "asocials", because their lives did not conform to the rules of the regime.

Lesbian women, for example, posed a threat to heteronormativity, as they defied social expectations by refusing to marry men and have children. They are poorly documented in historical sources, which has contributed to making them invisible. However, queer people have always been part of history, including that of the concentration camps.

Today we have a more developed language to describe queer experiences. In the early 20th century, transgender people were referred to as “transvestites” (a term coined by Magnus Hirschfeld).

A so-called “cross-dressing licence” allowed them to wear clothing of the opposite sex in public without fear of sanctions. It was even possible, in some cases, to change marital status. However, these licenses did not protect transgender people from paragraph 175. During the Nazi regime, in fact, they were suspected of homosexuality and therefore considered enemies of the state.

A significant example is that of Liddy Bacroff, defined at the time as a "transvestite". Bacroff, who lived as a woman in Hamburg, worked as a sex worker and had sexual relationships with men, which she openly declared. This led to her being arrested several times under paragraph 175. During her detention she wrote several texts, including “Freedom! (The tragedy of homosexual love)” and “A transvestite experience. One night stand in transvestite bar Adlon!”.

In 1938, Bacroff called for “voluntary castration.” A medical examiner declared her a “corrupter of morals” and “incorrigible.” In the same year she was sentenced to three years in prison, followed by preventive detention as a "dangerous repeat offender". Transferred to various penitentiaries, in 1942 she was deported to the Mauthausen concentration camp (Austria), where she was murdered the following year.

Lesbian women, while not directly persecuted for their sexuality, were excluded and targeted as “asocials” (black triangle). Since there is no specific category of detention for homosexual women, it is difficult to trace their stories. Patriarchal tendencies in historiography have also contributed to marginalizing research on queer women during the Holocaust.

Today, few documents remain relating to lesbian women in concentration camps. However, we know some names, such as that of Eleonore Behar. This young Jewish woman, deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto in 1945, fell in love with Anna Lenji, a young Hungarian. After the liberation of the ghetto by the Red Army on May 9, 1945, Behar emigrated with her mother to Chile, where she lived until her death in 2011. Anna Lenji still lives in Haifa, Israel.

Why are these stories important?

During the Holocaust, sexual desires and non-conforming genders were stigmatized in ghettos and camps. Survivors rarely spoke about them or, worse, were described as perverse monsters. Reconstructing the history of queer people is an arduous, fragmented task that requires further research. Even studies on homosexual men under Nazism are far from finished.

2023 was the 78th anniversary of the liberation of Europe from National Socialism. Remembering the Nazi crimes shows us the danger of hatred and indifference in the face of exclusion and the loss of the rights of others.

At a time when violence against queer people is on the rise, history teaches us that the fight for freedom, equality and respect must continue every day.

Original text: Here recherche des traces queers

January 27>Stories of pink triangles: the denied memory of homosexual homocaust